Mark Englebretson

Grade 4

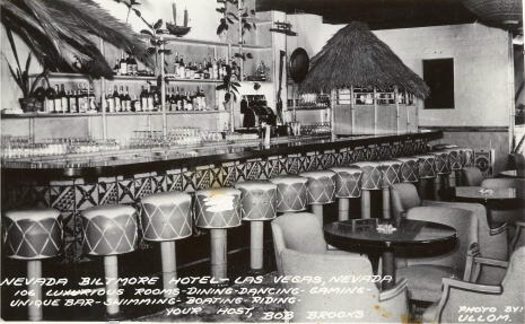

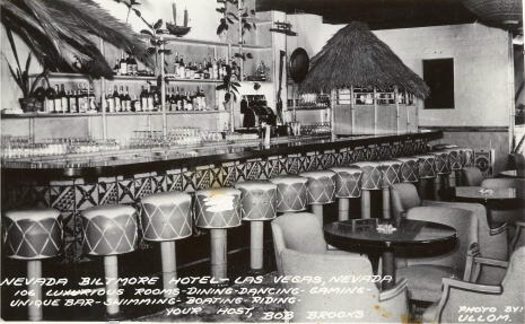

Photo from the Rick Olsen Collection

Photo from the Rick Olsen Collection

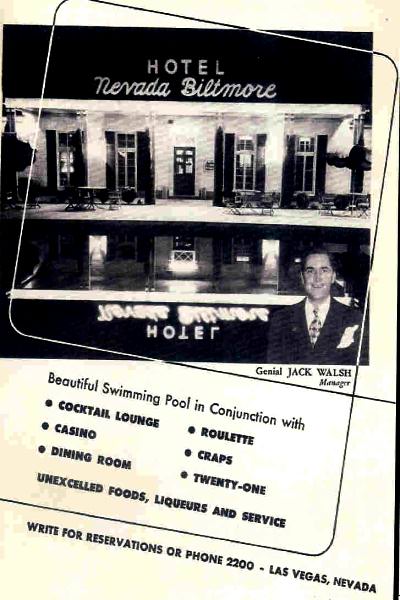

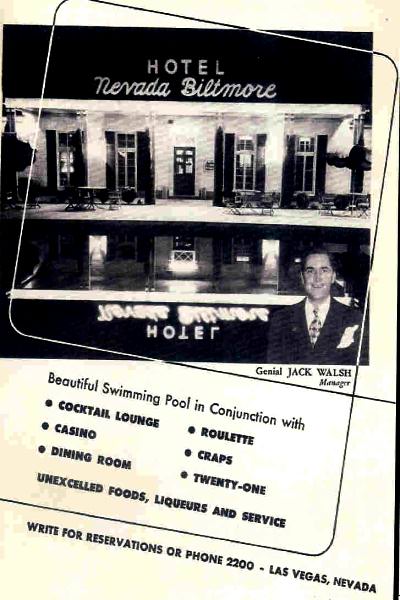

Ad from the Rick Olsen Collection

| Nevada Biltmore |

| 614 North Main @ Bonanza |

| 1942 to 1949 |

Mark Englebretson Grade 4 |

Photo from the Rick Olsen Collection |

Photo from the Rick Olsen Collection |

|

Ad from the Rick Olsen Collection |

|

| The Black Biltmore |

| For a few anxious weeks in 1949, the Las Vegas resort cracked the color barrier. Historian Bob Stoldal digs up fresh insights as to how and why it happened. The Moulin Rouge, the celebrated Las Vegas hotel-casino, took a noteworthy chunk out of the civil-rights barrier in mid-century America. It was perhaps the first hotel in America built for an integrated clientele, and certainly the first in Las Vegas, a city that had earned the nickname "Mississippi of the West." The Moulin Rouge was celebrated extensively during its mere six months in business -- it made the June 20, 1955, cover of Life magazine -- and it lives on today, romanticized because of the many articles, books, images and efforts to salvage its architectural remnants in the ensuing decades. But many of the steps in the long, hard climb toward equality were far less glorious. Most are completely forgotten. Such is the case with the Nevada Biltmore, a Las Vegas hotel-casino whose day in the spotlight occurred several years before the Moulin Rouge's and whose contribution to our history lasted not even half as long. Its story is complicated by behind-the-scenes machinations -- some involving prominent citizens whose names adorn our public buildings today -- and lingering questions, which is perhaps why the Biltmore's lessons have been lost beneath 60 years of dust. That, and there's not much left to remind us of the little resort that stirred up the town during the summer of 1949. All that's left of the Biltmore is a huge old palm tree in the middle of an otherwise bulldozed lot on the northeast corner of Main and Bonanza. The Biltmore was built on this corner in 1942 by Bob Brooks. His single-story resort on 17 acres -- featuring a hotel, cottages, showroom, casino, restaurant, bar and pool-was Polynesian-themed, a motif he'd brought with him from his famous Seven Seas restaurant and lounge in Hollywood. For nearly three years the investment paid off, thanks to business from the expanding Army Air Field at the north end of town. But by the end of 1944, Brooks saw the Biltmore's future dimming and sold the resort. It changed owners (one of whom was famed bandleader Horace Heidt) until June 1948, when four well-known members of the white community purchased the resort as the Nevada Biltmore Hotel Corporation. Lou Wiener Jr. was a prominent attorney who, at the time, was handling the will of his late client Bugsy Siegel; B. Mahlon Brown was a former justice of the peace; Jimmy Sills owned a drive-in restaurant; and Carl Amente was the gambler of the group. Together they decided to pursue a local clientele instead of competing for visitors with the hotels on what was becoming known as "The Strip." But in less than a year, the partners realized their plan was not working. A new approach was needed, and someone came up with the idea to turn the Biltmore-one of Las Vegas' six major properties -- into a resort serving the black community. During the 1940s, that community had grown from 178 to 2,888. Many blacks were recruited to work at the new defense plants here. Some were soldiers stationed at the air base or assigned to guard Boulder Dam. The Biltmore, two blocks from the railroad depot and near "the Negro section" of town, was in a good spot to reap the benefits, with business potentially coming from tourists and local residents. On April 21, 1949, as part of the plan, Wiener filed a new set of articles of incorporation for the aforementioned partnership, which was renamed the Texas- Nevada Corporation, and the documents listed him and two others as directors, including Cliff Jones, the state's lieutenant governor. With a capital authorization of $1 million, Wiener stated that the purpose of the corporation was to acquire, operate, lease and or dispose of resorts. The Biltmore was not mentioned, but the next day a man who was not named in the articles, Stanley Hunter, quietly filed applications for liquor and gaming licenses for the resort. Homer Snowden was not listed in those articles, either, but two days later, the prominent Texas oilman introduced himself to citizens of Las Vegas as the president of the Texas-Nevada Corporation and announced that he had purchased the Biltmore with his partners, whom he refused to name. He did tell the Las Vegas Review-Journal that Hunter would operate the hotel-casino. The Review-Journal and the Reno Evening Gazette each wrote articles about Hunter, describing him as a native Nevadan who had been active for years in the state's hotel business. What neither newspaper reported was that, before the war, Hunter had been escorted out of Nevada. In the late 1930s, because of financial trouble, he was forced to sell the Yucca Club, a gambling saloon on the outskirts of Las Vegas. Then he was arrested after breaking into the home of his estranged wife and threatening her and their son with a gun. The next day police put Hunter on a bus heading for Washington state, where he lived with friends. How or when Hunter became associated with Snowden, Wiener or Jones is unclear, but on May 1, 1949, Hunter took charge of the day-to-day operations of the Nevada Biltmore. Using the existing licenses from the original Wiener partnership, Hunter was able to sell liquor and keep the gaming operations open, pending state and local approval of his applications. Over the next month a series of strange events took place, starting with rumors that the owners of a major Las Vegas hotel-casino were negotiating to sell the property to a group of "colored entertainers." On June 9 the Nevada Tax Commission voted to delay issuing a gaming license to Hunter and the new Biltmore group "subject to investigation." The next day the whispered story became public: The possibility that a major Las Vegas resort would be sold to a group of wealthy Southern California black men was mentioned in the mainstream press. A nationally syndicated newspaper columnist, Erskine Johnson, told his readers on June 10: "Jack Benny's Rochester [Eddie Anderson] is bidding for ownership of the million-dollar Las Vegas Nevada Biltmore Hotel." In the 1940s, "Rochester," Benny's valet and confidante, was a household name in America. By 1949, Anderson was a star in his own right, making film, radio and live appearances. But four days later Hunter announced that he, not Anderson, had purchased the Biltmore. He told the Review-Journal that he'd negotiated the sale over the telephone with Snowden and his attorneys 12 hours prior to the alleged Anderson bid. What kind of ploy Hunter was involved in we'll never know, but one thing is certain: He never signed any papers. Hunter was fronting for Snowden, who was still the owner of record. Why? Perhaps it had to do with biggest news of the day. In that same front-page article, Hunter proclaimed that "the Nevada Biltmore is open to Negro local and tourist trade now." He made it clear that the Biltmore was not going to be an integrated hotel. The community was not ready for that, but it might be ready for a resort "operated for colored trade exclusively." The self-proclaimed new owner also said he was hiring "a complete staff of Negro attendants in the hotel." The white establishment was shocked; the city fathers were mortified. At that time, no black person was allowed to rent a room, buy a meal, place a bet or see a show downtown or on the Strip. Even those who came to Las Vegas to headline in the showrooms weren't allowed to stay in the hotels. The city was strictly "Jim Crow." The response was immediate. Mayor Ernie Cragin called the city commissioners to his office for a "special meeting" to consider Hunter's license requests. His first action was to have a letter read into the minutes from B. Mahlon Brown stating that he and his partners had "disposed of their interest in the Nevada Biltmore Hotel operation." On a motion of Commissioner Reed Whipple, the mayor and the commission unanimously revoked the original licenses. The next item was a motion, again by Whipple, to reject the liquor and gaming applications Hunter had submitted three weeks earlier. With a second from Commissioner Wendell Bunker, supported by the mayor and the other commissioners, Hunter's applications were denied. No reason was given. "Swank Vegas Resort Hotel Exclusive for Negroes Now; City Revokes Its Licenses" was the headline in the June 16, 1949, Nevada State Journal. The Reno Evening Gazette carried this quote from Hunter: "We acquired the hotel May 1, and it has been dying on its feet, so yesterday I announced it would be operated for colored trade exclusively. Yesterday afternoon the commission revoked our bar and slot machine licenses. That's discrimination, and I am going to court to get the licenses back." Hunter's charges were not printed in the Review-Journal, whose policy -- as editor John Calhan later said in his oral history -- was: "We were not interested in promoting racial problems. The newspaper was going to let nature take its own course, as far as the blacks were concerned. We were neither for nor against them." But five days later, the paper did have a story about the reaction from the "Westside Folks," who had swiftly rallied against the commission, saying the licenses were denied precisely because the Biltmore was being "converted into a colored operation." Woodrow Wilson, president of the Las Vegas chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), demanded answers. He called on Mayor Cragin to attend a public meeting on the evening of June 20 at the Second Baptist Church. One hundred people showed up, but the mayor was not one of them. Cragin was popular among the voters, having been elected twice (perhaps it helped that his insurance firm had just about every gaming club in town as a client). But he did have a previous run-in with the black community. He had opened the El Portal Theatre on Fremont Street, and despite pleas from the local NAACP chapter, kept the movie house segregated throughout the 1940s. In the Biltmore case, Cragin sent Wilson a letter saying he was sorry that neither he nor any of the city commissioners were able to attend the meeting. He invited the NAACP and its members to an "informal" commission meeting the next day. On the morning of June 22, Wilson and more than 50 supporters showed up. A Review-Journal reporter in attendance said Wilson, who would later become the first black to serve in the Nevada Legislature, made an eloquent plea to the commission "to preserve civil rights and respect minority rights in the Biltmore matter." Cragin's response was that the city commission had no right to refuse a gaming or liquor license to any person on the grounds of race, and he invited Wilson's committee to attend an official meeting on this issue. Wilson accepted. "A group of approximately 250 to 300 blacks followed me down," Wilson recalled in a 2004 interview with Las Vegas CityLife. "We marched on City Hall." Counting advocates and opponents of new liquor and gaming licenses, about 500 people showed up, forcing the commission to move from its regular chambers to a nearby auditorium. The meeting featured numerous appeals from citizens who wanted the city to change its policy of limiting the number of gambling and liquor licenses. They were denied, and so were licenses for the Biltmore and two other hopeful casino operators, including Benny Binion. Commissioner Whipple acted as a protector of the gaming industry, and pointed out that he was not alone: "A large number of substantial citizens have protested extension of gambling and liquor licensing. ...If this board was to throw the city wide open, it is reasonable to believe a concerted drive might result to eliminate all gambling in Las Vegas." Wilson called the Biltmore's setback "a really sad situation for the black community. It would have helped to raise the economic status of the community because that would have put blacks in positions of authority, management and the like by having people make the type of money that executives and sub-executives make in the hotel industry." "But," he added, "we continued to work." And this persistence proved to be a pivotal moment for blacks in Las Vegas. For the first time in the community's history, in June and July 1949, the Biltmore was the only first-class Las Vegas resort where blacks' money was accepted. From the hotel rooms to the recreation facilities, they were at last being served. Dedra Geran, a black resident, recalled on the City of Las Vegas' centennial website that during all those years of segregation in Las Vegas, the "white owner" of the Biltmore was "the only person in all of Las Vegas to let blacks swim at his hotel pool." And although the bar could sell only soft drinks, the Review-Journal reported that "Negro guests were permitted to bring their own liquor bottles for drinks in the dining room." Just as the Nevada Biltmore was getting into the swing, its tenuous financial framework began to fall apart. Snowden, who was behind on his payments, went to Southern California in late June to negotiate with Heidt, who held the mortgage. The bandleader wanted his money and was threatening to begin foreclosure proceedings. After several days of discussions with Heidt's attorney, Snowden called from Los Angeles on July 3 to tell the hotel staff that he had worked out a deal to avoid foreclosure. He didn't tell them that Heidt's attorney had said the deal would only work -- as the Review- Journal reported 10 days later -- if Snowden came through with a "sizable sum of money." The good news was that support for the all-black enterprise had come from the Central Labor Council of Los Angeles County, which asked Heidt to support the "colored" plan. The labor group, according to Review-Journal reports from Los Angeles, believed that "Las Vegas is a natural stopover between this city and Salt Lake City, and provisions should be made for colored tourists." But just five weeks after Hunter's big announcement, Snowden closed the resort. Heidt's Los Angeles attorney made a point of telling a Review-Journal reporter that the conversion of the hotel to an allblack resort had "no bearing" on Heidt's decision to foreclose, but the band leader "wants his money out of the hotel." In the July 19 Review-Journal, the community read about "the ill-fated operation of the Nevada Biltmore hotel as a colored resort" and how it had been relegated to "white elephant" status. Snowden went back to Dallas, and his front, Hunter, headed for Reno. For the rest of Las Vegas, it was business as usual. The Biltmore would find new owners, new managers and a new name -- the Shamrock. It reopened in 1950, but luck did not go with the name. Not long after, pieces of the property were sold, the pool was filled in, and the building became a furniture store. The night Snowden closed the Biltmore, Ella Fitzgerald made her first appearance in Las Vegas, opening at the Thunderbird Hotel on the Strip. Backed by her husband's group, the Ray Brown Trio, the singer was a hit in Vegas. A Review-Journal reviewer wrote that she was met with "thunderous applause that left no doubt that she is the top 'pop' singer of the nation." Where she and her musicians stayed remains a mystery. However, by this time in Fitzgerald's career, her manager, Norman Granz, was "using his commercial clout to combat racial injustice," according to Stuart Nicholson's 1993 Ella Fitzgerald: A Biography of the First Lady of Jazz. "Promoters seeking to book his concerts had to sign a contract that expressly forbade any kind of racial discrimination." This clause in her 1949 contracts included concerts in the South. So it is possible that Ella and her entire entourage broke another Las Vegas color barrier and slept on the Strip that very night. It's possible. But like many of those bold little steps in our past, the memories are fading and the facts are still buried. |