Audrey Welshans

Grade 3

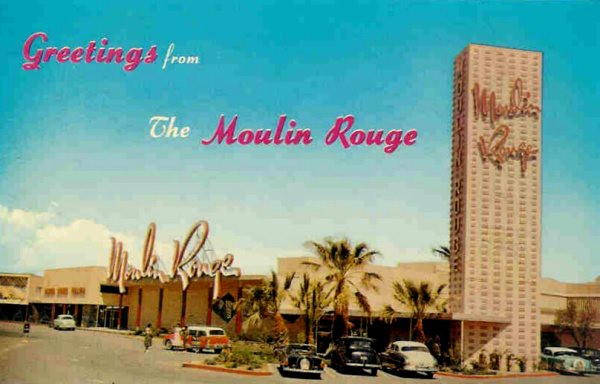

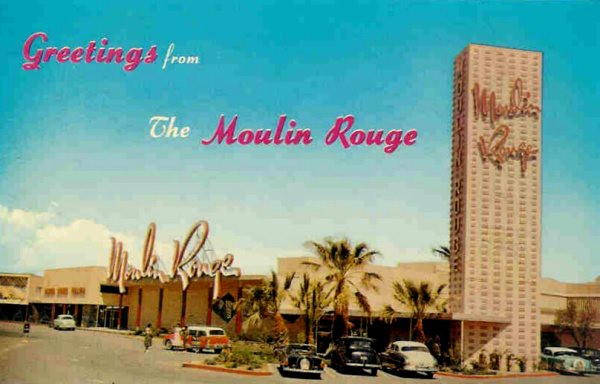

Photo from the Mark Englebretson Collection

Photo from the Mark Englebretson Collection

| Moulin Rouge |

| 900 West Bonanza |

| 1955 - 1959 |

Audrey Welshans Grade 3 |

Photo from the Mark Englebretson Collection |

Photo from the Mark Englebretson Collection |

The Other Vegas Remembering Vegas' Moulin Rouge Casino-the only hotel where blacks could gamble By Charles Fleming Less than a mile from downtown Las Vegas, only three miles from the glitzy, glittering Strip, is black Las Vegas. This is Westside, the heart of African American social and cultural life in this hot desert town. Las Vegas is booming. Black Vegas is almost dead. The Strip booms with crowds, new construction and the "ka-ching" of commerce. Here the streets are deserted. Shops and stores are boarded up. Signs ignored by the homeless read "No Loitering" and "$1.25 Quart Budweiser." Gusts of wind and stray dogs shoot down the sidewalk on Jackson Street, Westside's central avenue, where vacant lots that used to home to thriving businesses now glitter with the glass of broken bottles. At the corner of Jackson and F streets sits the New Town Tavern, Las Vegas' only black-owned casino-indeed America's only black-owned casino-and once the center of a lively black Las Vegas community. Inside, thick with the smell of spilled beer and stale cigarettes, there are empty chairs set before rows of computerized slot machines and video poker machines. The only gamblers, this day, are card players. A group of six elderly black men, wearing hats and smoking cigars, sits near the back of the small casino, quietly playing seven-card stud. On the wall behind them is a hand-drawn menu. It says, "Pork Chops or Smoked Neck Bones $5.95." There was a time when black Las Vegas, Westside Las Vegas, was not so bleak. There was a time when black Las Vegas, in fact, was the hippest, happiest, most happening place in the country. The time was May 1955, and the place was the Moulin Rouge Hotel and Casino. On Bonanza Road, set halfway between the center of Westside and downtown Las Vegas, the Moulin Rouge was a towering mecca for jazz music, exotic stage shows and the only hotel-casino in America where an African American could legally gamble. During the summer of 1955 the Moulin Rouge, advertised as "the first truly cosmopolitan hotel in this famous city," ran hot as the desert wind. Every night, on stage, it was Ella and Satchmo and Sammy and Frank. In the audience it was Bob Hope and Dorothy Lamour, Tallulah Bankhead and Harry Belafonte. White musicians and black musicians jammed on stage. Black gamblers and white gamblers hurled money at the tables. It was an ebony and ivory Camelot the likes of which America had not ever known, and has not known since. It lasted six months. Now the historic Moulin Rouge is struggling to rise again. Plans for a $3 million renovation and December 2000 reopening ended in nothing but broken promises. Canadian investor Bart Maybie, who bought the Moulin Rouge and many surrounding properties and has overseen several failed efforts at restoring the once grand hotel and casino to their original splendor, is once again bankrolling a plan to put the Moulin Rouge back together. As a Maybie associate says, "We have to. The history of the Moulin Rouge is not just the history of black Las Vegas. It is the history of Las Vegas itself. And there's not much of old Las Vegas left." Black Vegas began with black migration to Nevada in the 1930s, when laborers were needed for the construction of the mighty Hoover Dam. During the next decade, companies lured black workers from poor Southern towns to the high desert, where they were mining magnesium and other metals made valuable by wartime shortages. With the end of the war, however, the mines played out, and the black workers were left jobless. But construction of a new Nevada was under way. Gangsters run out of Chicago by Al Capone were realizing their dreams of a gambling empire in the desert. Hotels were going up. Black workers found jobs building, and then staffing the new hotels, restaurants, and casinos. Once employed, though, the workers had few places to spend their money, and no place to entertain themselves. Las Vegas was strictly segregated. The color ban prevented headliners like Sammy Davis Jr. and Pearl Bailey and Duke Ellington from eating, drinking, gambling or even sleeping at the hotels that hosted them. This was as true for the kitchen help as the front-room headliners. Sammy Davis Jr. may have been a big hit at the Sands, but if he wanted a cocktail or a craps game he went to the Westside. So did everyone else. Those there at the time remember Lena Horne and Pearl Bailey, Della Reese and Nat King Cole all performing on the Strip and then being bused, at the end of the night, back across the tracks, literally, to rooms in boarding houses. As Vegas grew, Westside grew, but it remained the town's black ghetto. Calvin "Eagle Eye" Shields was a musician on the road circuit in the '50s. His route, of what he calls the "top-notch white hotels," took him from Miami to Cuba to Puerto Rico to New York to the Catskills to Las Vegas. He remembers a thriving Westside. "It was booming here, during segregation," he remembers, "because blacks didn't have no place else to go. We patronized ourselves. We had to." The town's clientele may have insisted on segregation. Vegas in its infancy was reserved for high rollers-those who had the time to travel and the money to charter air flights into Vegas' McCarran Airport. Las Vegas was considered an elegant desert center. Men and women dressed-the men in suits and ties, always, and the women in cocktail or evening dresses and jewels-and the town's hoteliers laid on the best in entertainment and cuisine, coddling the high rollers, hoping they'd leave some of their money at the gaming tables. The casino settings were elegant. And white. The casino operators insisted on it. Claude Trenier, along with his two brothers, was Vegas' first successful black lounge act-and for years they were the city's most successful lounge act, bar none. Trenier remembers working at the Frontier, and the Riviera, and the Hacienda-and being thrown out of all three when he and his friends tried to get drinks at the bar. One night a customer sent a bottle of champagne to a table where Claude was sitting at the Riviera, between shows, with some friends. The owner told him to send it back. Claude refused. "I told them, 'If you put us out, you ain't got no show tonight.'" The owner relented. Claude and his friends enjoyed the champagne, and then he and his brothers took the stage for the second show. The following night he arrived for work and was told the Treniers had been fired. The reason: "They said we were drunk on stage!" Trenier says, more than 40 years later, with a huge laugh. Norma Miller was a dancer. She arrived in Vegas in 1942, before the Strip even existed, and by the 1950s was working the downtown clubs, appearing with Pearl Bailey in what she calls "a mammy-type act, with bandannas and all that," at the El Cortez. At the end of the night, she and Bailey and the other performers were forced to board a bus and leave downtown, before dinner, to take their meals and get their rest on the Westside. For years after, Pearl Bailey would headline Vegas hotels, but she was not allowed to drink or dine in the same hotel-restaurants. The Moulin Rouge, then, was a natural. A group of investors led by New York restaurateur Harry Ruben, opened the Moulin Rouge at a cost of about $2 million in May 1955. Ruben's managers had scoured the nightclubs of Harlem and Chicago's South Side for the best black dancers and singers, and had raided the Pullman train staffs for the best black kitchen and restaurant workers. They hired black waiters and bartenders, black maids and cleaning crews, black managers and black supervisors. (The only white workers were the dealers. Because there were no casinos in America that would hire blacks to deal, there were no trained black dealers in America. The casino had to make do with white dealers.) Out front, greeting the guests underneath a 60-foot-high neon Eiffel Tower, was retired heavyweight boxing champ Joe Louis. Then, as now, Vegas was booming. In the late spring of 1955, when the Moulin Rouge opened its doors, the Las Vegas Strip was lined with huge hotel-casino extravaganzas like the Sahara, Thunderbird, Flamingo, New Frontier and Desert Inn. The Riviera had opened in April, and the Dunes a month later. The newly constructed Hacienda and Royal Nevada Hotels were about to open, as was the now-forgotten Martinique. (The El Rancho Vegas property was shortly to go on the market for a mere $3 million.) On and around Glitter Gulch and Fremont Street, in downtown Las Vegas, the Overland, Apache, Sal Sagev and El Cortez hotels were soon to be joined by the Fremont and the Mint. There were already more than 2,500 hotel rooms in Las Vegas. A June 1955 Life magazine cover story asked the question, "Las Vegas-Is Boom Overextended?" Experts wondered, "Had Las Vegas pushed its luck too far?" No one suspected that the Moulin Rouge was pushing its luck at all. From opening night, it was a sensation. Norma Tolbert, a dancer who was on stage that night, remembers an evening of total elegance, thick with celebrities. "The showroom was also a very elegant dining room," Tolbert says. "There were linen tablecloths and candlelight. There was fine dining, and after dinner there was the show. I remember Frank Sinatra and Peter Lawford, and Sammy. And Tallulah Bankhead, and Ann Miller. And Edward G. Robinson. Everybody was there." Cary Grant was there that first night. So were Jack Benny and Milton Berle. So were some of the country's richest men and women. Says dancer Dee Dee Jasmin, who graced the stage that opening night and every night of the Moulin Rouge's short life, "It was very elegant. There were furs, and chiffons, and satins and taffetas. And all kinds of jewels. And lots of stars. On opening night, Harry Belafonte brought Tallulah Bankhead, and she became a regular." The real sensation of the Moulin Rouge was "the third show," also known as the "breakfast show." It kicked off at 2:30 a.m., and ran until 3:30 or 4 a.m., and it made the Moulin Rouge, and changed the face of Las Vegas permanently. Until that time the Strip hotels and the downtown hotels with entertainment offered two shows per night. The performing ended around midnight. Customers lured to town by the marquee-name entertainers were expected, at midnight, to spend some time in the casino. Most did, and this is where the businesses really turned their profits. The Moulin Rouge's third show idea was borrowed from other integrated clubs around the country. "All of the black and tans-the integrated clubs, you know-happened after midnight," says William H. "Bob" Bailey, the Moulin Rouge's first house singer and a longtime resident of Las Vegas' Westside. "Harlem, in New York, was after midnight. Central Avenue, in L.A., was after midnight. Chicago's South Side was after midnight. So we decided to do the same." "The idea of the third show was to accommodate the whites from the Strip," says Jasmin. What the Moulin Rouge got instead, she remembers, was "all the patrons, and all the musicians, and all the dancers. The Strip hotels forbade the white dancers from coming to the Moulin Rouge, but they came. Everyone came." "The stars would all come, and then they'd come backstage," remembers dancer Tolbert, then a wide-eyed 17-year-old dancing in the Moulin Rouge line. Tolbert says the word would spread like fire: "Get dressed! Frank Sinatra's here! And he'd come right into the dressing room. They'd all come backstage and tell us how much they'd liked the show." "Everyone" included the top black entertainers from the Strip hotels, for whom the Strip had nothing else to offer. They couldn't dine or game or dance or get a room. They couldn't watch their peers work, or work with them. Says Bailey, "There was no place on the Strip where the black musicians could sit in. There was no place where they could jam with their white friends. (The Moulin Rouge) was the only place where the musicians could get together." "It didn't matter who was playing," Miller remembers. "Pearl, Ella (Fitzgerald), Count Basie, the bus would come at 6 o'clock to take us to work, and we'd do two shows, and then we had to be out of there at midnight. We'd come back to the Westside-and bring everything and everybody with us. We'd do the 2 o'clock show, and it was jumpin'. It was one swinging affair." Within a short time, the mystique of the Rouge's late-night scene began attracting white folks down from the Strip, too. What they pursued there was not available at the Strip hotels-especially if they were white men pursuing black women. Jasmin and Tolbert say the Moulin dancers were the most beautiful, most exotic in the country. It was understood that they would "mingle" between acts, joining customers for drinks or dinner at their tables if invited. Says Tolbert, "The men did pursue the women-the white men, especially. I had so many white men pursuing me it was unbelievable." Says Jasmin, "The white guys came to the club to meet black girls. There were so many propositions it was unreal. I know 'cause I got some of them!" As a result, Trenier says, the Westside had more than a little of something for everyone. "I had more fun on the Westside than I ever had anyplace else in my life," he says. "We used to bring the showgirls from the Strip over here. They'd say, 'Ooh, if we get seen on the Westside they'll fire us.' So we'd put 'em in the car and lay a blanket over 'em! Man, we had fun." The nation's press jumped onto the Rouge bandwagon almost from the beginning. Life magazine, a month after the integrated hotel opened, did a Vegas cover story. A full-page photograph-under a snapshot of the Moulin Rouge's marquee, which promised a "Tropi Can Can" revue-featured the Rouge dancers doing a brand new dance routine. The caption indicated an "African dance called 'The Watusi' (which) brought the chorus line out in feather tails to writhe through a violent sequence of jumps and contortions." At the sequence's "climax," the caption reported, "a medicine man came bounding out brandishing two live squawking chickens." Competing acts that week included comedian Joe E. Lewis, at the El Rancho Vegas, actor Jeff Chandler, at the Riviera, Rosemary Clooney and Joey Bishop (and, in the lounge, Louis Jordan, who would later that year headline at the Moulin Rouge) at the Sands, and Tommy Dorsey at the Frontier. It was like nothing Las Vegas had ever seen before. The opening number was known as "Mambo City," and featured the desert's first-ever all-black chorus line. Jazzman Benny Carter and his orchestra was the house band. (Lionel Hampton would have the job by the end of the summer.) George Kirby was the "house comedian," and ran gags between shows. Two little boys known as Maurice and Gregory Hines were the opening act-doing a tap dance routine that Gregory would later make into an entire career. On succeeding nights, Bailey recalls, "It didn't rumble until after the third show, and then it really rumbled. At 7 a.m. Louis Armstrong was still playing, or Harry Belafonte was still on stage singing." As the summer rolled on, and the success at the Rouge continued, Lionel Hampton would become the house bandleader. Dinah Washington took the third show. Les Brown and his orchestra took over the house for the final weeks. The action never slowed. Segregation in the desert, at that time, was severe. One longtime resident remembers downtown clothing stores where a black man could not try on a jacket before purchasing it-because it would be too "dirty" to sell after he's worn it. Several others bring up the day that Sammy Davis Jr. impulsively jumped into the swimming pool at the Strip hotel where he was headlining. The following morning guests found the pool emptied of water and being scrubbed by a cleaning crew. Another time, Lena Horne announced that her husband and their daughter would be taking a swim. The pool was drained, and hung with a sign that read, "Pool Closed for Repairs." Bob Bailey remembers a night when he and Nat King Cole and the Sands Hotel's publicity manager walked into the Tropicana. The doorman stopped the men and refused them entry. The publicist protested, "That's Nat King Cole." The doorman said, "I don't care if he's Jesus Christ. He's a nigger and he has to get out of here." Curiously, though, it was not racism, but commerce, the killed the Rouge. When Harry Ruben and his Vegas associates were planning, building and opening the Moulin Rouge, those involved remember, it was designed to service blacks, which meant it would take no business away from existing business interests. "It was supposed to be this nice little black hotel on the Westside," Bailey says. "But now, because of the third show, it's competing with the Sands, and the Sahara!" Worse, the Rouge was competing with the Strip hotels during prime time-after hours, when all the hotel guests were supposed to be at the gaming tables losing large sums of money. That sealed the Moulin Rouge's fate. Within six months of its strong opening, with no evident sign of trouble, the Rouge would be closed. "One night we performed to a packed house. The next night it was padlocked," remembers Dee Dee Jasmin. "It was shut down. Why?" says Norma Tolbert, "We thought it would last forever, (but) we showed up for work one day and it was closed." No one today can adequately explain what killed the Moulin Rouge. Norma Tolbert believes that the Vegas powers wanted the Moulin Rouge out of business as soon as it opened: "We felt this constant threat of being shut down," she remembers. "There was the sense that the big people did not want a club of color to exist." Bob Bailey believes the investors, not anticipating overnight success, had poor financial backing from the beginning, and never improved it. The short-term banknotes they'd used to open the hotel proved their undoing: "When we started taking money away from the Strip, the notes all started coming due," he says. "Obviously there was pressure (from the big hotels)." Dee Dee Jasmin offers another idea: "It was a conspiracy, right from the beginning, and Mafia involvement, from the get-go," she says. "They took money out of there every single night, and never paid a single bill. It was all about money-laundering." Agrees Bailey: "There were rumors. Someone was skimming. Somebody was milking the pig." Whatever the case, when it was done, it was all the way done. The Moulin Rouge experiment was over. When the hotel closed, there was no place for the black stars and the white stars to get together. The black stars stopped coming. Then the white stars stopped coming. It was over. Says Bailey, "There was no place to meet after that. It all ended." Over the years there were several efforts to bring the Moulin Rouge back from the dead, but every effort ended in frustration or worse for those who attempted it. A year after the hotel's closure, the lights came on again at the Rouge under the direction of Richard Taylor, an ex-Hacienda Hotel manager. He opened the shuttered hotel for the 1956 Christmas and New Year holiday, handling the overflow from the Strip hotels. He tried the same gambit for Memorial Day in 1958. After that, the Rouge remained mostly dark. For a while it was a nightclub. For a while it was a hotel/motel. For a while it was a flophouse. By the early 1990s the property had fallen into such disrepair that even its future as a cheap hotel seemed uncertain. Police reports repeatedly identified the place as a haven of thieves and drug dealers. "Management tolerated drug dealers, (which) amounted to 50 percent of the Club Rouge clientele," one report said. Though the hotel and grounds had been granted a listing on the National Registry of Historic Places in 1992, and was thus spared the wrecking ball, the site languished until early 1998, when Canadian entrepreneur Bart Maybie bought the rundown Rouge for a reported $3 million. He had already purchased the adjacent Desert Breeze apartment complex, and planned a lavish reopening of the Moulin Rouge for the fall of 2000. It was not to be. Today, the Moulin Rouge remains a fixture on Bonanza Road. Its purple tower still rises, though the neon Eiffel Tower is gone. Inside, the ballrooms and casino space are crumbling with age. The neighborhood around it, too, is increasingly given over to marginal, storefront businesses. The surrounding blocks feature the Greater House of Prayer, and Big Mama's Soul Food Rib Shack. Almost next door, in front of the Las Vegas Rescue Mission, unemployed day-laborers wave at passing cars. |